THE OTHER SIDE OF THE COIN

Resisting Resource Extraction of Shimmering Industries

In my graduation project, The Other Side of the Coin, I delve into the colonial legacy of the Sorowako nickel mine in Indonesia—an industry deeply connected to my own family history. The materialization of my year-long research is an installation that aims to uncover the complex nature of nickel extraction while shedding light on the hidden costs borne by the indigenous communities of Sorowako.

The project seeks to make visible how we are interconnected with exploitative mining practices, which are deemed necessary for the so-called ‘green’ transition.The nickel industry in Indonesia is essential for producing batteries for electric vehicles and plays a critical role in the global shift from fossil fuels to renewable energy. However, if mining pollutes the land, displaces local residents, and perpetuates the injustices of colonial power structures, we must ask: how justifiable and sustainable is this transition?

The Sorowako mine, situated in the Sulawesi archipelago of Indonesia, is one of the world's largest nickel mines. The coveted nickel in the mine is stored in the layers of earth just below the surface of Sorowako, above which lie extremely biodiverse forests. To extract the ore, humans and non-humans in the landscape are ruthlessly displaced to make way for strip mining. Nickel refineries dump their toxic cooling water on the land and the air is polluted with dust and soot, while dangerous mudflows are created due to the displacement of earth.

The Karonsi'e Dongi and Sorowako communities, who live near the mine, have been resisting the nickel industry for decades, striving to preserve their indigenous way of life even as their existence becomes increasingly entwined with the sprawling nickel operations. The demand for nickel has skyrocketed in recent decades, driven by a global push for a "green utopia" powered by electric vehicles. Yet, it is the indigenous communities of Sulawesi who bear the burden of this relentless expansion.

Established in the early 20th century, the mine was initially part of the Dutch broader colonial plan to convert raw materials and labour from its colonies into profit. The Dutch goverment funded geographical and mineral research by the TU Delft to document the earth around Sorowako. Leader of the expedition, Dutch mining engineer E.C. Abendanon argued in his book and later papers: “The volume of nickel ore in the Verbeek Mountains will make the Netherlands Indies one of the richest nickel-producing countries in the world” (1918).

This colonial agenda resonates deeply with my own family's history. As my grandparents' their love story in Indonesia laid the foundation for my family. When my grandfather, Herman, lost both parents after World War II and sought a new life. He was appointed manager of Ruhaak & Co, a Dutch company importing industrial machines to Indonesia and exporting raw materials back to Europe. During a brief leave in the Netherlands, he met my grandmother, Elly, and they instantly fell in love. From this moment, an ‘exotic’ Dutch love story unfolded in Indonesia, intertwined with the ongoing injustices of Dutch colonialism that framed their relationship.

My family's story, perhaps like yours, is an alloy of romance, industrialization, resource extraction, colonization, and revolution. When viewed alongside the development of the Indonesian nickel industry, this raises urgent questions about the materials we use in design. It highlights the historical injustices surrounding the global distribution of these resources, reminding us of the importance of recognizing and amplifying the often-overlooked stories of resistance. In embracing these stories in design and realizing our role within them, we create space for a broader understanding of the personal stories between land and design.

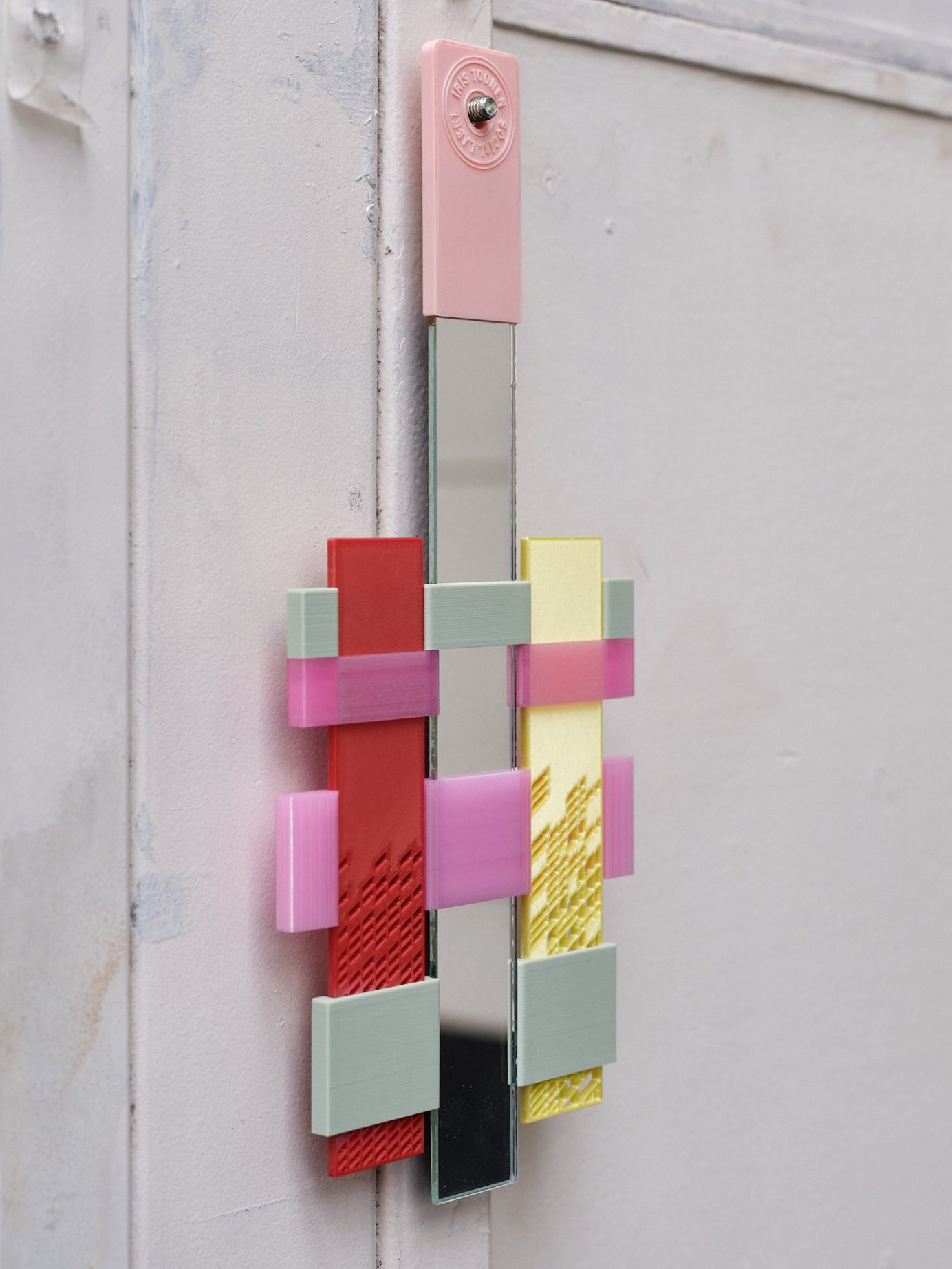

The culmination of my year long research is an installation that uses vinegar and electrolysis to transform Dutch Guilders into a new currency, symbolically revealing hidden histories.

Electrolysis, a chemical process in which an electric current triggers a reaction, enables nickel particles to migrate from one surface to another. Here, Guilders made from Indonesian nickel are immersed in vinegar alongside a copper-coated silicone mold. When connected to a power source, the electric current corrodes the coins, dissolving their Dutch imagery and transferring the nickel onto the mold to create new coins.

Graduation project Master Industrial Design 2024: Royal Academy of Art the Hague. In collaboration with Tracy Glynn

Exhibited at:

Royal Acedemy of Art 2024, The Hague

TROEF gallery 2024, Leiden

Young designers space 2024, ‘s-Hertogenbosch

Royal Acedemy of Art 2024, The Hague

TROEF gallery 2024, Leiden

Young designers space 2024, ‘s-Hertogenbosch

Published in the BNO Dutch Design yearbook 2024

Best Graduates

Awarded the Fonds Pop-Up Stimuleren

Makersklimaat grant 2024